from Penelope Farmer, writer of the novel Charlotte Sometimes at

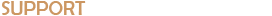

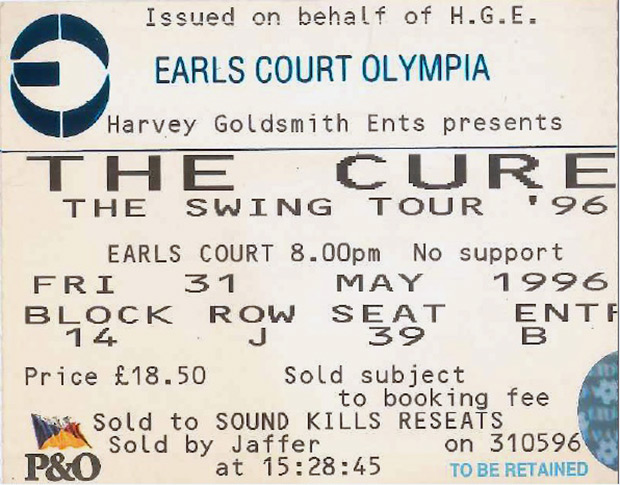

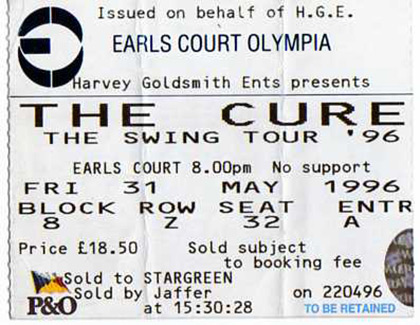

grannyp.blogspot.comThe Cure themselves went quiet for a while, They issued some new albums from time to time but did not tour. But in 1996 I think it was, I saw that they were going to tour again, starting with a huge gig at Earl's Court just up the road from Hammersmith where I was living. I decided to try and get tickets; to get myself backstage if possible, to meet the Cure themselves; in particular to meet the group's lead singer and song writer, Robert Smith. It wasn't easy getting in touch with them; even when my agent and I managed it between us - discovering in the course of this that The Cure's base was in a building they'd named 'Charlotte House' - the management was deeply suspicious. The law had changed by now, moral ownership was acknowledged, they appeared to suspect I was going after them again. Finally my agent and I convinced them this wasn't so. They agreed: yes, there would be tickets for me at the Box Office. And yes if I came early and went back stage, I would be allowed to meet Robert Smith himself.

And so it was I offered the second promised ticket to my twin sister's daughter, my niece, born a year after the book came out and named, appropriately for the evening, 'Charlotte' (if I so much as hinted that she might have been called after the fictional Charlotte, my sister would rise up out of her grave to clobber me, so I won't). On a June evening - or was it July?- we set off together for Earl's Court for my - if not Charlotte's - very first - and probably last - rock concert.

Earl's Court is ENORMOUS. And noisy - or so it seemed to me. But then the only times I'd been there before was for the Royal Tournament - an entertainment now, thankfully, defunct - either as a child or, later, with a wargame-mad son. There were a lot of bangs in that. But rock concerts, I suspected, come much louder.

Charlotte and I had been told to present ourselves an hour before the show was due to start. We picked up our tickets, and were led out of the entrance area and through into a cavernous space, the wide but not very tall screens separating one section from another making it appear still higher, still vaster. It was so much beyond any human scale that the group waiting in the same space as us looked dwarfed, like as yet unconnected cogs in some industrial metropolis. There was nothing to sit on, or lean against. It was dusty, I think. If not it looked it. Various other people came in and out. Someone who seemed to be in charge of the group admonished them from time to time, bossily but cheerfully.

We waited a long time. More people came, more people went. Apart from us, only the group stayed put. We were told that the people were American Cure fans from the mid-west, winners of some competition for which the prize was a trip to London, tickets for the Earl's Court gig and a meeting beforehand with The Cure themselves. All of them were clutching record sleeves, photographs, all of them were looking awed and excited, chattering among themselves in rather frantic American voices

Time went on. It was not until almost time for the sold-out concert to start that the whole of the Cure sloped in between two of the screens; sloped really is the right word, I promise you - slouch might have been near too; but 'slope' is better. Some of them clutched instruments; they had quite a lot of hair between them. They looked pretty much as you'd expect a pop group to look, not that I'd had much experience. The American group converged on them giving little shrieks. Pens came out, record sleeves and pictures were signed, the group smiled in a bored kind of way: clearly this wasn't their favourite aspect of the job. Why should it be?

Even so it took up a lot of time. The time the gig had been advertised to start was well past already.

I'd given up hope of anyone coming near us. Charlotte, shifting from foot to foot, was looking at me and shrugging. I was looking at my watch again, ruefully, and shrugging back. But then quite suddenly, everyone disappeared - the group of fans, the Cure, the watchful functionaries, the security guards, everyone; everyone but Robert Smith that is, who was sloping towards us (yes, 'sloping' once again will do it) hair on end, lipstick smudged, a beer can in one hand, and in the other a very tatty copy of the first paperback edition of Charlotte Sometimes. It was a Puffin book and the picture on the front was of two little girls: the only girly-looking edition of the book ever, and the very last one I would have expected him to be holding.

'Hi,' he said, thrusting it towards me. 'Could you sign it for me, please?'

He opened it up: from the first page onward, line after line had been underlined in pencil. 'You see how inspired I was,' he said, adding behind his hand, looking at me sideways, 'how I nicked it.'

I laughed, I couldn't help it. Then I signed, as requested, with more than the usual flourish. 'To Robert,' I wrote, 'love from Penelope.' And added my whole name to the title page, the way writers do.

Robert Smith apologised for the beer can. 'I have to keep my throat in good shape,' he said. Then he apologised for not being able to play the song in the main part of the concert, 'We've got to publicise the new album, you know. We'll play it as encore,' he said. 'I promise.' Underneath the lipstick, the standing on end hair, the Gothic everything, I can promise you, wombats, that Robert Smith really was just a nice, not to say very nice, very well brought-up boy from Sussex who not only loved his long-term wife but also probably loves -or loved - his mother.

Even eleven years older, he probably still is a very nice boy at heart. Why shouldn't he be?

Then he told me the story of how he'd come across the book in the first place.

'My elder brother used to read to us at bedtime,' he said, 'I was about twelve or so and he was still reading books to us. Your book was one of them, it never got out of my head. Once I got into music I wanted to make a song about it. That's how it happened.'

We didn't mention copyright. I admitted I liked his having written the song, and we agreed it might be nice to be in touch again, in slightly less rushed circumstances. 'Have to go. I'm running late' he said and sloped off, still clutching his beer can, still clutching his tatty copy of Charlotte, now with my signature inside. And 'Love from Penelope.'

I can't quite say the concert was an anti-climax. Unlike some later Cure concerts that year it got lousy reviews in various places; among other things there was a lot of trouble with the sound system. Yet it still seemed amazing to me, from my innocent standpoint, much more noisy even than Royal Tournament, and much more spectacular, lighting-wise, though I wasn't so sure about the music (I gathered afterwards it was far from their best album). I suppose it would have seemed tame to anyone who's ever seen Madonna, which I hadn't and still haven't except on television, briefly. But it didn't seem tame to me. The way the sound, the light, took me over, thrummed through me, physically, was outside anything I'd had experienced before. It was thrilling, as opera can be thrilling, though in an entirely different way. (Still, probably, I prefer opera. Sorry about that.)

The band went out and came back before the encores. And then it happened. A few familiar chords sounded; everyone started cheering. Robert held up a hand - stilled them - 'you all know the song', he said - more cheers, but stifled - 'this evening,' he went on, 'the writer of the original book is here in the hall with us.' The cheers rose again and he didn't stop them this time as the lights swung round to where Charlotte and I were sitting and picked us out. People craning round to see, I got up, put up my arms, waved my hands about and acknowledged them; the first and - certainly - the last time I'd get that kind of buzz, the kind rock stars are used to, but writers most certainly aren't, even the best known ones. Then the chords swelled up again, the cheers faded and I sat back and listened with everyone else to what was by now, even to me, something deeply familiar, even effecting in its way. My tune you could say; yes, really.

thanks to Robert R.

thanks to Robert R. thanks to Robert R.

thanks to Robert R.

thanks to Pillowman

thanks to Pillowman